(General Studies II – Polity Section -Functions and Responsibilities of the Union and the States, Issues and Challenges Pertaining to the Federal Structure, Devolution of Powers and Finances up to Local Levels and Challenges Therein. Salient Features of the Representation of People’s Act.)

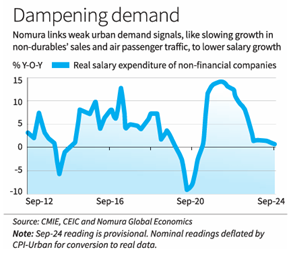

- The 2024 Lok Sabha elections in India highlighted the soaring costs associated with campaigning, sparking renewed discussion around electoral funding, transparency, and the influence of wealth on democratic processes.

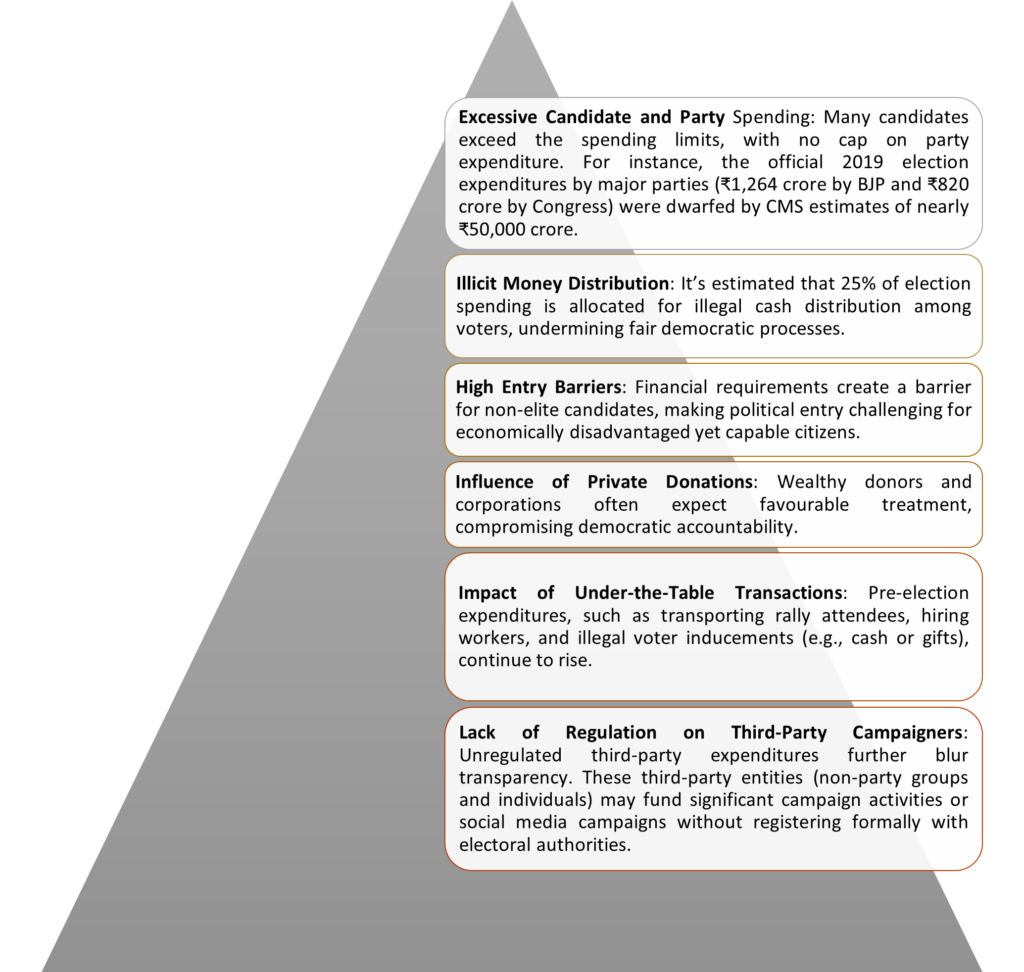

- Expenditure in this election cycle exceeded ₹1.35 lakh crore, over double that of the 2019 elections, underlining the growing financial pressures and issues around transparency in political financing.

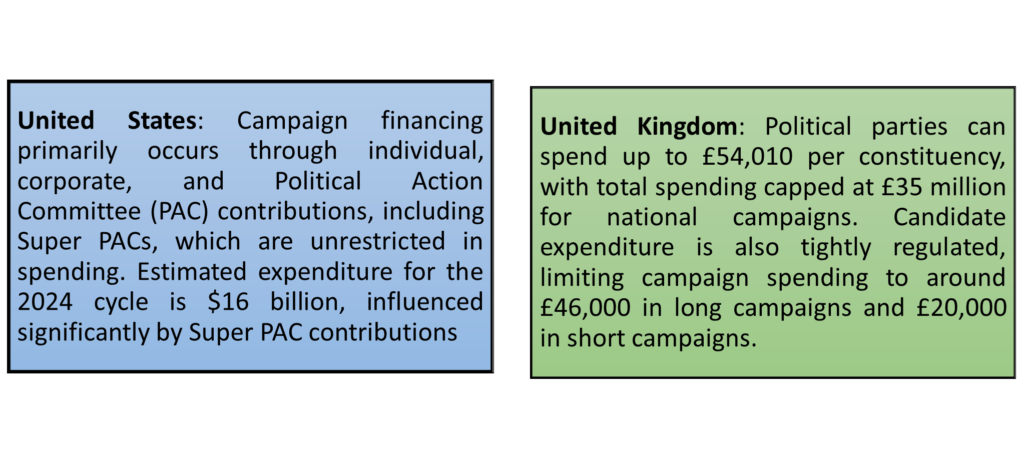

| Election Financing Rules in India Election financing in India is primarily regulated by the Representation of the People Act (RPA), 1951, which mandates that every candidate maintain accurate records of campaign expenses. Section 77 of the RPA requires candidates to keep detailed records of their expenditures, with non-compliance resulting in possible disqualification under Section 10A. The Election Commission of India (ECI) has set expenditure limits for individual candidates to control campaign spending, with the 2024 limits at ₹95 lakh for Lok Sabha candidates in large states and ₹40 lakh for Assembly candidates. |

Recommendations for Reform –

- State Funding of Elections: Proposed by the Indrajit Gupta Committee (1998), this model could involve either direct financial support or non-monetary benefits like free media time or public transport. State funding could be limited to recognized parties to reduce costs and ensure fair distribution.

- Establishment of a National Election Fund: Advocated by former Chief Election Commissioner T.S. Krishnamurthy, a National Election Fund could centralize political donations, allowing transparent and regulated funding. Funds would be allocated based on electoral performance and adherence to democratic principles, thus avoiding the need for parties to solicit individual donations.

- Limitations on Third-Party Campaigning: Indian electoral laws lack provisions for third-party campaigners. Regulatory frameworks should mandate reporting requirements and spending limits for third-party entities to prevent excessive unaccounted spending.

- Ceiling on Party Expenditure: The ECI has recommended a cap on total expenditure by political parties proportional to the candidate expenditure limit multiplied by the number of candidates fielded. This measure could deter parties from exceeding acceptable limits through indirect spending.

- Enhanced Transparency Requirements: In the PUCL v/s Union of India (2003) ruling, the Supreme Court endorsed the need for statutory audits and transparency. The ECI should enforce mandatory public disclosure of donations over ₹20,000 and provide accessible formats for parties and candidates to submit expenses for easier monitoring.

- Elimination of Election Freebies: Freebie promises often distort voter behavior and divert resources from critical services. Electoral authorities could explore pre-election restrictions on major new welfare scheme announcements, reducing their influence on voter behavior.

- Digital Tracking and Modernization: Given the proliferation of digital media, campaign spending, including social media ads and third-party endorsements, should be closely monitored. The ECI could consider partnering with social media platforms to trace and limit paid political content, ensuring transparency and compliance with spending limits.

| Reforming India’s election financing will require political consensus, improved enforcement of expenditure limits, and a multipronged strategy. Addressing these systemic challenges is crucial to fostering a more equitable and transparent electoral system that limits financial influence and upholds democratic integrity. |

.